Arthur’s Adult Life

The Crucial Years

The next decade must have been central and crucial for Arthur’s subsequent career and it is frustrating to have so little information about this period. What is also of interest is the influence that Arthur’s elder brother, Edmund, must have had upon Arthur’s development.

The next specific information there is about Arthur is that he became a student at Cambridge University. Thanks to the assistance of the College archivist we know that the archives of St Catharine’s College, Cambridge record that Edmund Blackburn* Stringer, Son of Henry, Born June 14, 1869, at Sheffield, was Matriculated Non-Collegiate, Michaelmas, 1892. He then migrated to St Catharine’s College, 1893. Then Arthur followed his brother and in Michaelmas 1893, Arthur Blackburn Stringer Matriculated Non-Collegiate. He was subsequently admitted at St Catharine’s, October 10, 1894 as a Choral Exhibitioner. Non-collegiate students were those who were attached to hostels founded in the late nineteenth century with a view to providing less expensive access to the university of Cambridge by an avoidance of college fees. So presumably both Edmund and Arthur were non collegiate students in their first year but were matriculated into the University of Cambridge for their final two years. They then proceeded to St Catharine’s as members of that College. Presumably Arthur would have graduated in the Summer of 1896. For information about the college see, here.

Arthur will have gone up to Cambridge when he was about 21 which will have been older than the age of normal undergraduate admission. One has to assume that both Arthur and Edmund continued with their academic studies after qualifying as teachers and working as teachers while living in the terrace house in Barnsley before going to the university. At that time they will have needed to be proficient in both Latin and Greek to matriculate into Cambridge. Who taught them and where did they study in order to reach the educational standard for Cambridge matriculation? They will also have needed to have been active members of the Church of England. In addition since Arthur became a choral scholar he will have been an excellent musician and presumably an active member of a church choir. While at Cambridge Arthur gained his half-blue for athletics to add to his academic and musical achievements.

That both Stringer boys managed to gain entry to Cambridge In the late 19th Century is by any standards a considerable achievement. There were only about 800 students at Cambridge at that time and most of them will have come from public schools and prosperous middle class backgrounds. However, in the late 19th Century Cambridge was reforming and opening up to its wider social obligations, for an online history of St Catharine’s see here. This may have provided the social and more enlightened context in which the Stringer boys who left school at 13 were able to matriculate into the university.

Arthur would have come down from Cambridge in about 1896. Presumably he returned to work as a teacher. Although one cannot be certain. For instance his brother continued to reside at the University after graduating. Edmund is recorded as still being a student at St Catharine’s College on the 1901 Census.

In 1899 Arthur married Alice Maud Gray at Oxford. It is impossible to know when and how he met his wife, Maud, see here. It may have been when she was living in the North of England or training to be a teacher somewhere. Or while he was a Cambridge student he may have met her in her home town of Oxford when visiting or competing there in sports activities. The only ascertainable information is that they married in 1899. Arthur’s brother, Edmund, married his wife, Edith Spence Eagling, at Cambridge in 1901.

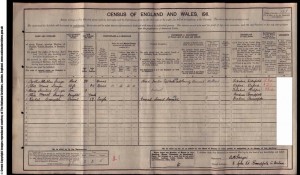

The 1901 Census provides the next information about Arthur’s career. He was recorded as living at 2 Akeds Road, Halifax, in the household of Alexander Reekie a dress and mantle maker. The house appears to be a more prosperous and substantial home compared to his childhood homes. Arthur was married and classified as an instructor of pupil teachers.

Maud, his wife of a couple of years, was not living with him. The census indicates that Alice Maud Stringer, a teacher, was boarding at 33 Bartlemas Road, Headington, Oxford. The house belonged to Ann Hubbard, aged 89.

They cannot have remained separated for long because their first child, Henry Staniland Stringer (Harry), was born in 1902 at Halifax. Thus presumably sometime in 1901 Alice moved north from Oxford and the couple were living in Halifax with their baby.

* There are a couple of records where Edmund is also given the second name of Blackburn, I do not know if this is an error or whether both sons were named Blackburn.

County Durham and Ferryhill

According to the 1911 Census Arthur Stringer, then aged 38, was living in a six roomed house, 6 Syke Road, Burnopfield, County Durham, with his family, namely: his wife, Alice Maud, 34; his eldest son, Henry Staniland, 9, who was at school; and our future mother, Alice Muriel, aged seven months. Also living in the house was Rachel Crompton, 17, classified as a general servant, domestic. This would have been in no way unusual at the time. There was nothing unexceptional about a typical non-manual family having a servant in the early 20th Century. Indeed it was a mark of middle class status to have at least one servant. Alice was born at Lanchester which is about seven miles from Burnopfield, perhaps there was a cottage hospital there. Arthur was classified as headteacher, Pupil Teacher Centre, and was employed by the County Council.

There is still a 6 Syke Road in Burnopfield but I suspect that the current building may have been rebuilt or renovated from Arthur’s day. Burnopfield had been a small rural community but developed during the 19th Century with the establishment of two large coal mines.

The brother, Edmund Stringer, had a career similar to Arthur. On the 1911 Census Edmund B Stringer, aged 40, was recorded as married to Edith, aged 33. They had a five year old daughter and another aged two months. There was a domestic nurse, 18, and domestic servant, 14, living in their seven roomed school house. Edmund was headmaster of a school in Hartsfield near Tunbridge Wells. The only school in Hartsfield today is a small Church of England Primary School. Edmund died in 1953 in Bridge, Kent, and his wife, Edith, died in Brighton in 1964.

In 1911 Arthur’s parents were still alive and living at 50 Hampton Road, Sheffield. The house still stands and is a substantial eight roomed terrace house and they were living there on their own with one lodger.

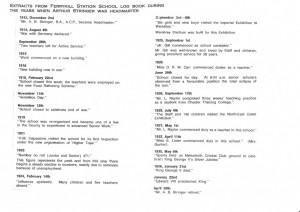

In December 1913 Arthur and his family moved some 20 miles south from Burnopfield to Ferryhill when he was appointed headmaster of Ferryhill Station School. He remained there for 23 years until his retirement. Maud, his wife, was a teacher there for some time and their daughter, Alice, also attended the school for a while. Family myth has it that on one occasion she complained to the headmaster, her father, about her class teacher, her mother. The school must have been an establishment very different from what we can imagine nowadays. For instance in 1908, 529 children were housed in eight rooms and in 1909 the teacher in Standard 1 is recorded as teaching over a hundred children with the help of a standard V11 girl. Legend has it that Maud used to teach a class of more than 60 educationally subnormal children The extracts, below, from the school log book during the time when Arthur was headmaster give a flavour of school life.

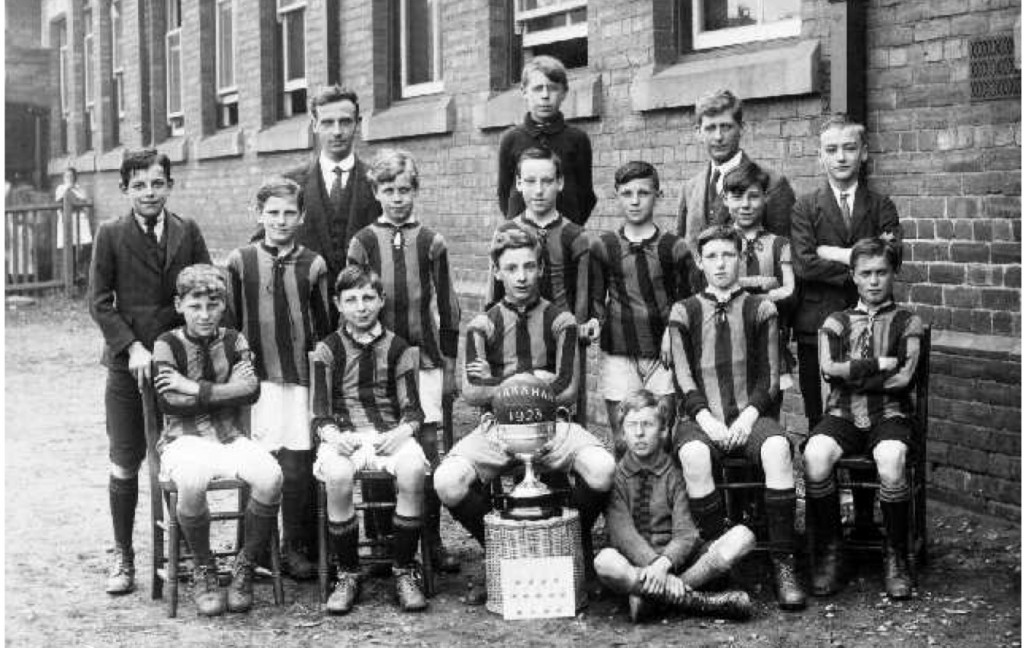

The photograph below is the only one found of Arthur during his working life. He is second from the right on the back row. He looks like a man of quiet authority and determination. Note the girls segregated in their own playground in the background on the far left.

Arthur Stringer with the Ferryhill Station School football team.

Ferryhill Station is actually a suburb of Ferryhill a mile or more from the main village it boarders pleasant countryside but the road and area leading to the school are drab and rundown, see the picture below.

Ferryhill Station School still continues to this day as a primary school and I took this photo of the building on a recent visit to County Durham.

I can vaguely remember once while we were staying in Harrogate as young children aged eight or nine maybe, certainly in short trousers, that we were dragged up to Durham on a tour of the parents’ old haunts. We visited Ferryhill Station School and I am reasonably certain that we were told that the tall house standing behind the school was the old school house where Arthur and his family had lived during the time when he was headmaster there, see the picture below. It is a substantial three story house and in Arthur’s day would have been a very attractive property to live in and I imagine that there would have been one or more resident servants.

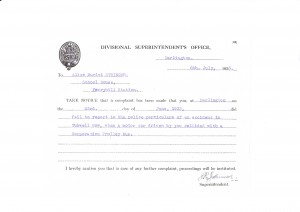

One incident from the Ferryhill years provides an insight into changing social circumstances at the time. In 1933 Alice Stringer received a Police Notice for failing to stop after an accident when she drove a car into a corporation trolley bus at Darlington. For some reason she kept this Notice all her life – she was probably rather proud of it and she retained the copy all her life, see below.

The letter is addressed to The School House, Ferry Hill Station School. The 1930s was the first decade when the possibility of car ownership was available to the middle classes. As prices of small cars steadily dropped more and more people from professional and managerial backgrounds began to acquire cars for commuting and pleasure. Also more women were learning to drive, see here. This suggests that Arthur had become reasonably prosperous and was able to afford a car and that the family were mobile around the Durham region and further afield. Also Arthur must have been reasonably enlightened, for the time, to allow his daughter to drive. Tubwell Row leads onto High Row and the photograph, below, taken in 1926 suggests that it will have been quite an achievement to collide with a trolly bus, given the traffic conditions at the time.

In 1936 Arthur, aged about 65, retired and moved with his wife to 31, Staunton Road, Oxford. He died in Oxford in 1960 and his wife died there later in the same year.

Comments

A few possibly gratuitous comments.

First, something I do not understand and which niggles me. Why did Arthur move to County Durham and especially to Ferryhill? Arthur must have been an educationist of some considerable ability and talent. There could not have been many headmasters of elementary schools at that time who were Cambridge graduates. For example, between 1878 and 1978 there were nine headmasters at Ferryhill Station School and only one of them, Arthur, had a degree. By the age of 38 he had become a head teacher responsible for training pupil teachers. He had experienced living in large industrial cities and Cambridge and his wife came from Oxford. He was a man familiar with city life and the academic world of England’s two ancient universities. Edmund had moved to Hartsfield which is a pleasant rural community near Tunbridge Wells in the south of England.

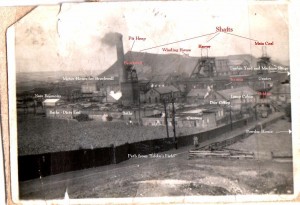

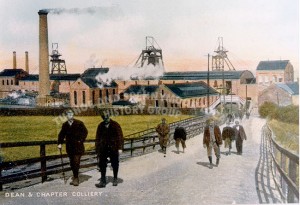

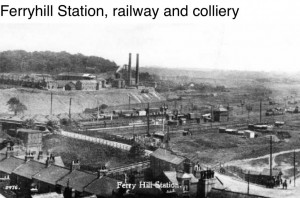

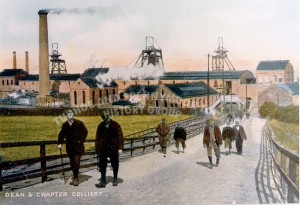

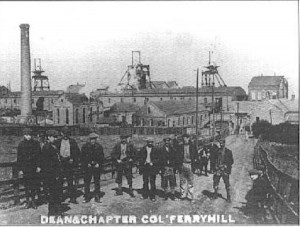

Put simply, why did a man with Arthur’s qualifications, he was also an Associate of the College of Preceptors, educational experience and expertise and cultural background decide to move to an unfamiliar part of the country, namely County Durham? First to Burnopfield, an unremarkable coal mining village, and then to Ferryhill. One wonders why he did not become head of a more prestigious establishment in a more pleasant part of the country. Old photographs of Ferryhill in the early 20th Century depict it as a somewhat dull, sprawling, provincial coal mining township with little to commend it beyond being close to the Cathedral City of Durham and lying on the old Great North Road. It did have pleasant countryside close by and it was not far from the coast. At the time when Arthur moved there it was, however, a rapidly developing mining area. For an informative history of coal mining at Ferryhill see here. The population of the village increased from 3,123 in 1902 to 10,674 by 1921. For photographs of Ferryhill during the Stringer years are included below but for a fuller library see here and here.

The Dean and Chapter colliery was the main mine in the village and a detailed history can be seen here. The lists of accidents and injuries during Arthur’s time illustrate the appalling working conditions. A few examples are listed below.

| Bolton, Richard, 14 Sep 1916, aged 39, Hewer, he was pony putting in the Harvey seam when a fall of stone buried both him and the pony | ||||||

| Bott, William, 05 Feb 1938, aged 50, Buried: York Road Cemetery, Spennymoor | ||||||

| Brain, Albert, 22 Nov 1927, (accident: 21 Nov 1927), aged 39, Hewer, killed by a fall of stone, Buried: York Road Cemetery, Spennymoor | ||||||

| Brown, Philip, 18 Oct 1956, aged 55, Wagon Lowerer, he was working on the surface when he was struck and run over by four trucks, he died in Bishop Auckland General Hospital shortly after being admitted | ||||||

| Bulmer, George, 13 Oct 1939, (accident: 09 Oct 1939), aged 31, Hewer, killed by a fall of stone | ||||||

| Bunn, Robert, , [date unknown] | ||||||

| Burgess, Thomas, 01 Nov 1945, aged 25, Putter, killed by a fall of stone, Buried: York Road Cemetery, Spennymoor | ||||||

| Burke, James, 25 Feb 1922, aged 66, Buried: Duncombe Cemetery, Ferryhill | ||||||

| Burns, R., 03 Jan 1933, (accident: 23 Dec 1932), aged 27, Run Rider, struck by rail | ||||||

| Caghill, John, 02 Dec 1907, (accident: 19 Nov 1907), aged 35, Stoneman, when drilling a hole in a top canch, the back end of the canch left up on the left side of the road dislodged the timber, and, falling upon him, broke his spine | ||||||

| Calvert, Robert, 31 Oct 1910, aged 61, he had finished his shift in the Brockwell seam and was returning to the shaft with the other men; they entered a refuge hole when some tubs were going to pass, and as he sat down he died; death was due to rupture of the heart |

So why did Arthur move his family there when he was already a headmaster? Perhaps it was a significant promotion, perhaps his working-class background made it difficult to find a post in, say, a grammar school, perhaps it was political or missionary commitment to better the lot of the people in the mining community, perhaps he saw it as a thriving and developing community, perhaps he wanted to remain in the north reasonably close to his parents. His father lived until 1935 and his mother until 1934, both died at Sheffield. Once established in Ferryhill it may have been difficult to leave even if he had wanted to. The year after the family’s arrival in 1914 the First World War started and afterwards there were periods of economic depression. Perhaps he thrived and enjoyed his time at the school.

Second, what I find remarkable is that Alice Muriel, our mother, had at least seven aunts and uncles on her father’s side and I, for one, never knew that any of them existed. What is also strange is that our grandfather, Arthur, had an elder brother, who was our mother’s uncle, and who had a very similar career to her father. Indeed it may be said that Edmund ‘led the way’ in that he joined the University of Cambridge before Arthur and became a headmaster like Arthur. I, at least, knew nothing of his existence even though, for instance, he did not die until 1953 when I was fifteen.

Third, it does make me at least wonder if here we have an explanation for the McNamara side of the family to cling to the Raeburn myth, see here. Nana, the daughter of a miner and with uncles who were miners and who was married to an ex sawyer’s apprentice was up against a family with two Cambridge graduates who both became headmasters and, as will become evident later, a mayor of Oxford in the offing. She will have needed to get some pedigree from somewhere.